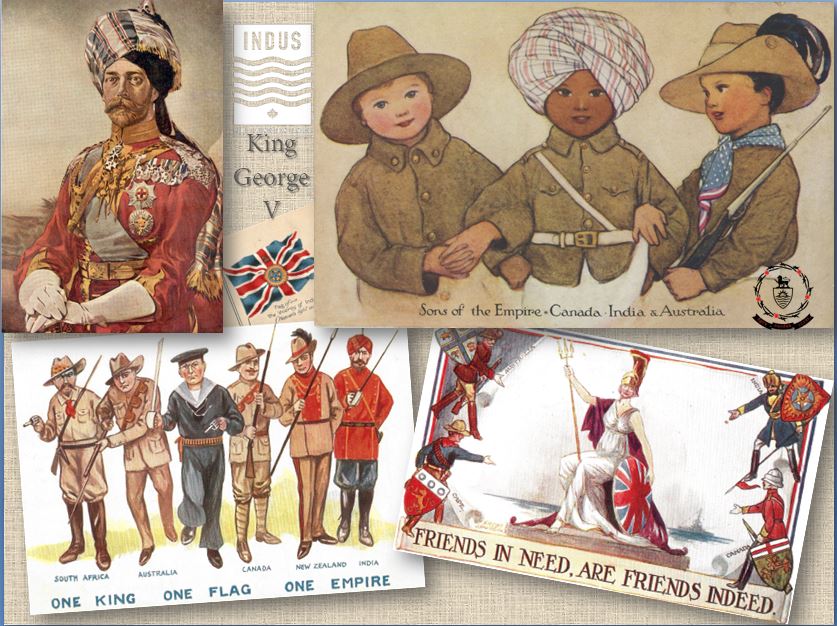

Sons of Empire, Brothers in Arms & Friends in Need

Posted April 26th 2015

In Remembrance of the men of the British, Canadian, ANZAC & Indian Expeditionary forces that lost their lives 100 years ago in Flanders and Gallipoli.

When war broke out, men of the Punjab were first to land in Europe to reinforce the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) in Flanders. In October 1914, the Kaiser had taken direct aim on the town of Ypres and the port of Calais, calculating by destroying the British force he would be able to take France quickly out of the war. His grand scheme had not factored in the Punjabis – the Lahore Division as fate would have it arrived in the nick of time to reinforce the BEF taking up 1/3 of the British line. In the words of Major Gordon Corrigan, author of ‘Sepoy in the Trenches’ and guest speaker on our 2014 Remembrance Day public lectures – the Indians “saved the British Expeditionary Force from annihilation in 1st Ypres.” The first German offensive on Ypres was defeated.

On 25th April 1915, the Allies launched an assault on Turkey’s Gallipoli peninsula with the aim of advancing onto Istanbul to take Germany’s key ally out of the war. Amongst the attacking force were 15,000 Indian infantry and artillery men. The ill-fated attempt was a disaster, all told casualties amounted to nearly 25,000 British and Irish, over 7,200 of the Australian units, more than 2,300 of New Zealand’s forces, and more than 1,500 members of the Indian Army.

April 25 is commemorated every year down under, as Anzac Day. Celebrating the “Anzac spirit” of endurance, the festivities annually etch the sacrifices of Australians and New Zealanders at Gallipoli into national consciousness as the cornerstone on which their nations are built. If you were to cut through the fog of time, you find Punjabis along with Ghurkas campaigning gallantly amongst their Anzac brothers in the thick of the fiercest fighting at Gallipoli. A Times of India report of 1915 detailed how the 14th King George’s Own Ferozepor Sikhs led a gallant charge uphill against well entrenched Turks. They took the trenches but lost over 80% of their battalion in the action. “The Sikhs & the Ghurkas were professional soldiers, at times they were the only ones that knew what they were doing” reported the good Major at our Vancouver Remembrance day community lecture last November.

Meanwhile on the same day, 25th of April 1915, on the famous sector of the Western Front in Belgium, men from the same Sikh heartlands of the Punjab, comprising the Jullundur and Ferozepor brigades were marching to reinforce Canada’s frontline in Flanders. Between April 22 -25th the Canadians held strong thwarting Germany’s second advance on the town of Ypres. Decimated by poison gas and superior German artillery they hung on desperate for reinforcements having lost 6,000 men. The next day on the 26th April, those reinforcements arrived. After an overnight march of 35 miles, from their own sector in Neuve Chapelle (French Flanders), the 47th Sikhs of the Jullundur brigade led a charge by the Lahore Division to take back Mauser / Geddes ridge adjoining Kitchener’s Wood. The harrowing ordeal is documented in their War Diary:

>>

“The country to be crossed was open, and devoid of cover; for the first 500 yards, it rose slightly to a crest, thence dipping for another 500 yards, and ascending in a glacis-like slope to the German position. Units had only the vaguest idea as to the position of their objective. Our Artillery fire was meager and ineffective, the Gunners having no better information than us as to the objective.

The Brigades came under shell and rifle fire on crossing the ST.JEAN — WIELTJE road, and on reaching the first crest the fire of all kinds, including tear shells, was terrific. As was inevitable, direction was soon lost The enemy’s fire was overwhelming, casualties were very heavy and the attack was held up No reinforcements reached the front to give fresh impetus. Small parties from various Regiments pushed on gallantly, working forward to within a few of the enemy’s trenches.”

<<

The battalion of 47th Sikhs lost 350 of 445 men that went into battle that day. Writing after the war, in a 1919 magazine, Lieutenant-General Sir James Willcocks Commander of The Indian Corp would remember the heroic action as the maiden battle honour for the regiment , reporting that “Few battalions in His Majesty’s Army can show a higher percentage of losses throughout its service in France than this fine corps, which so worthily upheld the traditions of the Khalsa.”

On the left flank of the 47th Sikhs, was the 57th Wilde’s Rifles Punjab frontier force spearheading the attack for the Ferozepor Brigade. They were equally exposed to the murderous German arsenal, as attested to by the entry for April 26th in their War Diary :

>>

“The position of assembly was some 1500 yards from the German trenches, which were on a ridge, the ground over which we had to advance was practically bare of all cover and completely commanded by the ridge, about the last 500 yards being up a slope, during this time a very poor bombardment had been carried on at the German trenches.

We came under a perfect hail of five, machine gun rifles, shrapnel and high explosive filled with asphyxiating gas. From here onwards men began to drop at a great rate, and we began to lose formation owing chiefly to the men bunching together behind each scrap of cover after every forward rush … the remainder being unable either to combat or understand the gas, turned and went, as it was no good stopping to be mowed down by machine gun fire and bombs.”

<<

The Lahore Division was employed as a whole, or by brigades, from 26th April until the 1st May in holding the Canadian portion of the frontline. In doing so, the Indian Corp lost in killed, wounded, and missing, 133 British officers, 64 Indian officers, 1620 British and 2070 Indian rank and file a total of 3887 all ranks, or 30 per cent of the infantry strength engaged.

Sir H. Smith—Dorrien (Commander of British Second Army at the Second Battle of Ypres. noted the disadvantages under which the attack was made on the 26th of April ” — insufficient Artillery preparation, on our side, and an open, glacis like slope to advance over in the face of over-whelming shell, rifle, and machine gun fire, and the employment of poisonous gasses by the enemy, and that in spite of these disadvantages, the troops, although only partially successful in wrenching ground from the enemy, effectually prevented his further advance, and thus ensured the safety of YPRES.”

Men from Canada and India that fought in the 2nd Battle of Ypres can be found buried or commemorated side by side in 17 memorials and cemeteries across the French and Belgian countryside. Many years after the end of WW1 , Marshall Ferdinand Foch, the French General credited with the final Allied victory, remembered the gallant actions of Canadians at Ypres:

” … it is as the men who saved Ypres when it seemed at the mercy of the enemy that the Canadians will live in history. For days the enemy rained on those devoted Canadians a weight of metal such as had never before been hurled at men in battle. Not content with that the enemy let loose poison gas and liquid fire. One might have been pardoned for thinking that there was here a combination that human nature could not prevail against, but the Canadians were there to repeat the old lesson that the capacity of the human soul to endure for a great cause has not yet reached its limit. ”

The Canadians were clearly cast as heroes. But who exactly were the ‘slave soldiers’ of the British Indian Army, foolishly throwing away their lives so far away from home in a conflict not of their making? These men were heroes answering the call of duty and upholding their personal, regimental and country’s Izzat /Honour ( WW1 was at the time widely supported across India). However, the gallantry and sacrifices of the Indian Army have never been fully dignified in remembrance and so their efforts have been open to muddying by political agendas. Post 1947 independence politics of India & Pakistan, and ‘well’ meaning left leaning academics in the West, railing against the vagaries of colonialism would have us believe that cowering Punjabi men were shepherded in their droves to the mouth of the canon in an imperial conquest.

This is a disservice to the honourable and brave men of the British Indian Army , whose actions, if you care to discover them, reveal volumes about them and their motivations. Our previous posts have covered the unique insights into their lives & motivations afforded by the censor’s letters – a fundamental belief that Germany’s war mongering threatened King & Crown, rallied their fervent support in the ‘Great War for Civilisation’. By every measure these were honourable men and gallant soldiers; wherever duty called, the Indian Corp fought bravely, upholding the ties of loyalty to the Crown and the bonds of brothers on the battlefield. Their actions won 21 Victoria Crosses (VC) during WW1. In addition to the prestigious VC, many Indian soldiers were also awarded decorations such as the Military Cross, Order of British India, Indian Order of Merit, and the Indian Distinguished Service Medal. In total over 9,000 gallantry awards were made to the Indian Corp, Indian men upheld their Izzat and that of India day in day out through some of the darkest chapters of the Great War. Today, let us honour the deeds of courage on one such day, April 26th 1915.

Award of the Victory Cross:

Jemadar Mir Dast, I.O.M., 55th Coke’s Rifles (Punjab Frontier Force), attached 57th Wilde’s Rifles (Punjab Frontier Force)For most conspicuous bravery and great ability at Ypres on 26th April, 1915, when he led his platoon with great gallantry during the attack, and afterwards collected various, parties of the regiment (when no British) Officers were left and kept them under his command until the retirement was ordered. Jemadar Mir Dast subsequently on this day displayed remarkable courage in helping, to carry eight British and Indian. Officers into safety, whilst exposed to very heavy fire.

Awards of the Indian Order of Merit (IOM)

The IOM was the Indian equivalent to the VC prior to 1911, and was second only to the VC for Indian troops during WW1. On April 26th the 3rd Lahore Division won the following IOM’s for gallantry and devotion to duty :

Jemadar Mangal Singh 57th Wilde’s Rifles (Punjab Frontier Force)

Mangal Singh received his award for gallantry during the 2nd Battle of Ypres, on 26th April 1915: “On recovering consciousness after being gassed, in spite of intense suffering, he went out time after time and helped to bring in the wounded under fire”. Mangal Singh was a native of Amritsar.

Sepoy Atma Singh 57th Wilde’s Rifles (Punjab Frontier Force)

Awarded for gallantry during the Second Battle of Ypres on the 26th April 1915. “Atma Singh, one of a machine-gun detachment, helped to bring a gun up to near the firing line and got it into position under a hot fire. Here he held on until the front line was driven out by gas but he himself declined to budge until lieut Deeds ordered him to retire.” Atma Singh was a native of Lahore.

Jemadar Sucha Singh 47th Sikhs

“On April 26th, 1915 during the 2nd battle of Ypres Sucha Singh took command of his company when all the British Officers were killed or wounded.” Sucha Singh was a native of Lahore.

Sepoy Bakshi Singh 15th Ludhiana Sikhs :

The I.O.M was awarded for the Second Battle of Ypres on the 28th April 1915. “During this attack, communications had as usual been cut by shells and when it was urgently necessary to get a message through, it had to be carried out by hand . Sepoy Bakshi Singh twice volunteered to take messages over a space of some 1500 yards, which was literally swept by fire. On both occasions he was successful and returned with the replies. On the 1st May he again distinguished himself by going out several times to repair the telephone wires which has been cut by shells.”

100 years ago, gallant actions such as these on 25th & 26th April, spread across 2 critical theatres of war were unparalleled. After all, what single community can claim to have had the ‘back’ of Britain , Canada and Australia during these critical do-or die moments early in the war – only the Punjabis; they were there at the moment of need, as sons of Empire, brothers in arms and friends in need.

For that, they should be remembered.